As we settle into the 21st century, mental health challenges are becoming increasingly urgent. The way we are ‘feeling’ is becoming more important to society and our daily lives. With mental health already being one of the defining challenges of our time, the World Health Organization (WHO 2022) estimates that depression and anxiety cost the global economy over $1 trillion annually in lost productivity. With accelerating change – technological, environmental, and social – these pressures only become more intense. By 2050, how will we support mental wellbeing in an era shaped by automation, climate change, and digital immersion?

Using Wendell Bell’s futures studies framework of possible, probable, and preferable futures (Bell 1998), we can begin to imagine what mental health might look like in 2050—and what could be done now to shape it for the better.

The Possible

Possible futures include everything that could happen, regardless of probability. These ideas can be radical, and sometimes dystopian, but they are all grounded in current knowledge or emerging technologies.

In one possible future, mental health could be entirely managed by artificial intelligence. For example, advanced biosensors in wearable technology or neural implants could monitor mood fluctuations in real time and intervene before a human therapist or psychologist is even aware. Emotionally intelligent AIs might even provide on-demand therapy, monitoring cortisol or dopamine levels, and adapting the way they approach their patients based on learned therapy techniques. In this world, people could be constantly monitored and might never have to suffer in silence again.

Another possible future is more concerning. If climate change and inequality continue to worsen, we could face a global mental health crisis. The Lancet Countdown (Romanello et al. 2021) has warned that extreme weather, food insecurity, and displacement is already linked to rising levels of PTSD, depression, and anxiety, especially among young people. By 2050, mass climate migration, job loss due to automation, and digital overexposure could create what some researchers have called a “mental health pandemic” (Hayes et al. 2018).

These visions are not implausible. Studies already show that AI chatbots like Woebot and Wysa provide cognitive behavioural therapy with measurable results (Inkster et al. 2018). Meanwhile, companies like Neuralink are developing brain-computer interfaces that could one day assist in treating neurological disorders (Musk 2019). On the darker side, global suicide rates remain highest in low-income countries (WHO 2022), while studies have linked climate change to rising mental illness rates (Cianconi, Betrò & Janiri 2020). If we fail to intervene, these trends could easily become much worse by 2050.

The Probable

Probable futures are those most likely to occur if current trends continue. They are often shaped by policy, economic investment, and technological advancement already in motion.

By 2050, mental health care is likely to be hybrid, blending AI platforms with human practitioners. Digital therapeutics, already approved by regulatory bodies in the United States and Europe, will very likely become mainstream (Torous et al. 2021). Apps and VR programs could help people self-manage their anxiety, PTSD, and phobias, while therapists could use the data created from these programs to manage their care in real-time. Access would likely expand significantly, especially in rural and low-resource areas.

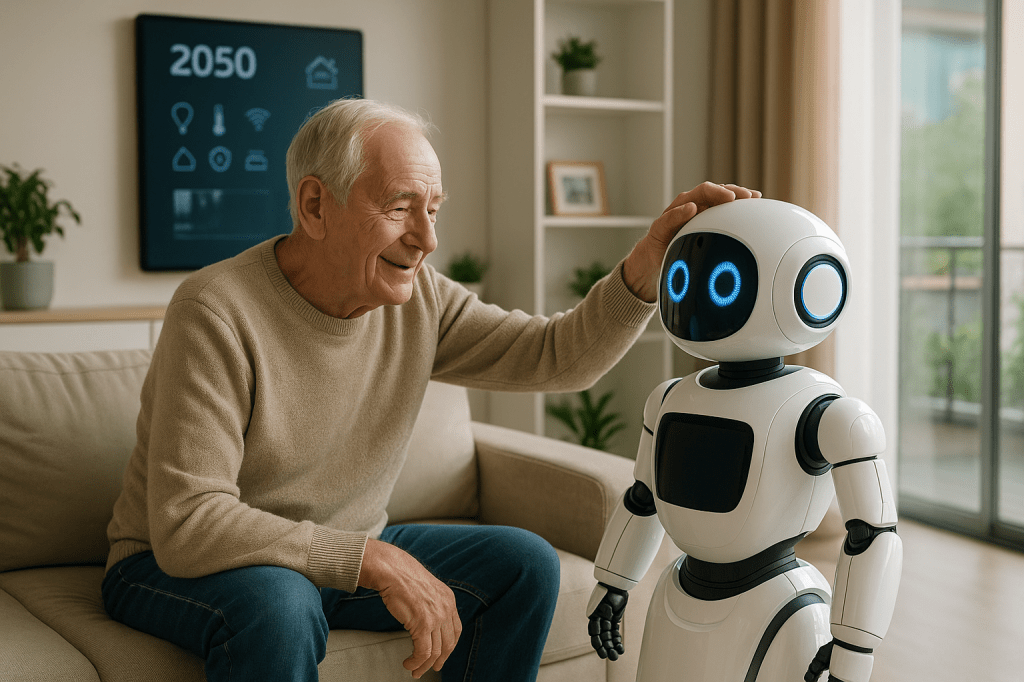

Demographically, the global population will also be older. The UN projects that one in six people will be aged over 65 by 2050 (United Nations 2019). This will bring new challenges such as increased rates of dementia, social isolation, and elder depression. However, technological solutions like robot carers and AI companionship will likely be used to mitigate loneliness (Broadbent et al. 2018).

Mental health parity, giving equal weight to mental and physical health, is likely to improve through policy and digital innovation. However, global inequities will likely persist. Just as today’s telehealth boom has benefited wealthier, developed nations, future mental health technologies could deepen divides unless efforts are made to include marginalised populations (Patel et al. 2018). The surveillance risks of biometric data, particularly in countries with weak data protection laws, will also remain a key concern.

The Preferable

Preferable futures are guided by values. They ask not what will happen, but what should happen. In a preferable future, mental health is embedded into everyday life, not just treated reactively, but supported proactively across the globe.

In 2050, mental health should no longer be stigmatised. From school curriculums to workplace policies, emotional well-being must be prioritised. Universal basic income or shorter work weeks, once fringe ideas, should now be in place, reducing stress and allowing people to pursue meaningful activities that provide happiness to them. Urban design should support mental health, with cities built around green spaces, 15-minute neighbourhoods, and quiet zones. Digital platforms should be designed to have a focus on wellbeing, rather than engagement.

Community support must also become key again. While AI and tech can help scale services, they will never replace human care. Peer-led networks, culturally sensitive care models, and localised healing practices should all work alongside high-tech solutions. Rather than a one-size-fits-all approach, A preferable future would embrace cultural, societal, and personal differences.

Experts like Richard Layard (Layard & Clark 2014) argue that policies that promote wellbeing, such as investing in mental health prevention and education, can deliver huge societal returns. Preferable futures must therefore be created not just by governments or tech companies, but by communities, artists, educators, and everyday people.

Conclusion

Looking toward 2050, the future of mental health could take many different paths, shaped by changes in technology, society, and the environment. Wendell Bell’s framework helps break down these possibilities—whether it’s imagining what might happen, what’s likely to happen, or what we’d ideally like to see. Possible futures introduce ideas like AI-powered therapy and brain-monitoring devices, while probable futures suggest we’ll keep seeing digital tools and blended care becoming more common. Preferable futures shift the focus to how wellbeing might be built into our daily lives, from city design to education and policy.

How mental health services will change from now will depend on the choices made by nations and policymakers along the way. Mental health in 2050 will likely reflect a mix of progress, new challenges, and changing priorities across different parts of the world.

References

Bell, W 1998, ‘Making People Responsible’, American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 323–339.

Broadbent, E, Garrett, J, Jepsen, N, Li Ogilvie, V, Ahn, HS, Robinson, H, Peri, K, Kerse, N, Rouse, P, Pillai, A & MacDonald, B 2018, ‘Using Robots at Home to Support Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial’, Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 20, no. 2.

Cianconi, P, Betrò, S & Janiri, L 2020, ‘The Impact of Climate Change on Mental Health: A Systematic Descriptive Review’, Frontiers in Psychiatry, vol. 11, no. 74, pp. 1–15.

Hayes, K, Blashki, G, Wiseman, J, Burke, S & Reifels, L 2018, ‘Climate Change and Mental health: risks, Impacts and Priority Actions’, International Journal of Mental Health Systems, vol. 12, no. 1.

Inkster, B, Sarda, S & Subramanian, V 2018, ‘An Empathy-Driven, Conversational Artificial Intelligence Agent (Wysa) for Digital Mental Well-Being: Real-World Data Evaluation Mixed-Methods Study’, JMIR mHealth and uHealth, vol. 6, no. 11.

Layard, R & Clark, DM 2015, Thrive : the power of evidence-based psychological therapies, Penguin Books, London.

Musk, E 2019, ‘An integrated brain-machine interface platform with thousands of channels’, BIoRxiv.

Patel, V, Saxena, S, Lund, C, Thornicroft, G, Baingana, F, Bolton, P, Chisholm, D, Collins, PY, Cooper, JL, Eaton, J, Herrman, H, Herzallah, MM, Huang, Y, Jordans, MJD, Kleinman, A, Medina-Mora, ME, Morgan, E, Niaz, U, Omigbodun, O & Prince, M 2018, ‘The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development’, The Lancet, vol. 392, no. 10157, pp. 1553–1598.

Romanello, M, McGushin, A, Napoli, CD, Drummond, P, Hughes, N & Jamart, L 2021, ‘The 2021 Report of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate change: Code Red for a Healthy Future’, The Lancet, vol. 398, no. 10311.

Torous, J, Bucci, S, Bell, IH, Kessing, LV, Faurholt‐Jepsen, M, Whelan, P, Carvalho, AF, Keshavan, M, Linardon, J & Firth, J 2021, ‘The Growing Field of Digital psychiatry: Current Evidence and the Future of apps, Social media, chatbots, and Virtual Reality’, World Psychiatry, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 318–335.

United Nations 2019, World Population Prospects 2019, United Nations.

World Health Organization 2022, Mental Health, World Health Organization.

Leave a comment